The Growth of Online Social Networks in the Real World

In Tim Berners-Lee on Social Graph: Ok, I Give Stowe Boyd takes Berners-Lee to task for confusing concepts and terminology related to “semantic web,” “social network,” and “social graph.”

I share some of Boyd’s confusion, partly because of the technical nature of some of the concepts, and partly because I sometimes can’t tell when an author is referring to networks based on “real” relationships or to networks based on relationships that exist only electronically.

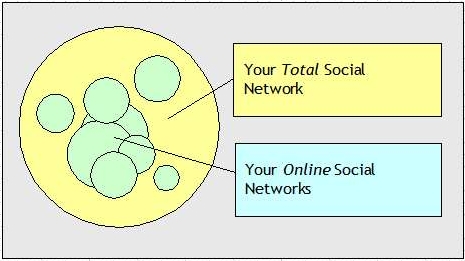

Maybe this is an old fashioned distinction. Sometimes I still think of social networks in two categories, with one a subset of the other:

Two Super Classes of Social Networks

In this diagram, “your total social network” refers to all the people that you know and/or have relationships with. The subset “your online social networks” consists of people with whom you interact electronically through some sort of an organized online group or community.

Personally, I know and have relationships — of some kind — with more people than are members of the online social networks I also belong to. Also, when I hear terms such as “social graph” that seem to be referring to a totality of relationships, I know that many details of relationships are never captured by any online online system.

Other people may have different views. Some may feel, for example, that they know and interact with many more people via online social networks than they meet and interact with “in the real world.” For example, think of those Linkedin members with thousands and thousands of contacts!

The concept of “online social network” can itself be confusing. Online social networks as they operate now (e.g., Facebook) operate as electronic “clubs.” They provide relationship- and communication-based benefits once you become a member of the “club” and agree to behave according to certain rules that exclude non-members from participation. This is not that different from the way that clubs operate in the real world.

Proposed standards such as OpenSocial are designed to make it easier to move from one online social network “club” to another by enabling transportability of certain types of information that are especially relevant to social networking.

Alex Iskold provides a good (albeit overly optimistic) overview of OpenSocial’s potential in R/WW Thanksgiving: Thank You Google for Open Social (Or, Why Open Social Really Matters). The reason I say “overly optimistic” is that, even though clever and elegant technical solutions may be created that simplify personal control over portable subsets of identity and relationship information, there will also be many individuals and institutions who will attempt to make evil or nefarious use of the portability benefits of OpenSocial. This fact will reduce the utility of online social networks for certain types of relationships and transactions.

For example, in The Truth About Viral And Social Marketing? Its All About The Sock Puppets from Deep Jive Interests, we see examples of how business interests already “game the system” by taking advantage of how social networking based ranking and linking behaviors can be manipulated. Won’t the ease of transporting identity and relationship information from one online network to another also simplify the creation and use of artificial identities, bogus relationships, and fake ratings?

The suggestion that you need to be wary of who it is you interacting with online is a good one, as far as it goes. That presupposes that you can in fact know who it is you are interacting with online and that you have the basis for assessing the level of trust and confidence you will ascribe to the message you are receiving.

It’s this aura of “trust and confidence” that may be the saving grace for specialized social networks in the face of the “flattening” that standards such as OpenSocial might inadvertently promote. Networks that do a better job of keeping out fakes and protecting valid relationships will gain reputation and trust, factors that can translate into member loyalty, subscription payments, and advertising dollars.

Granted, there are instances where individuals willfully choose to interact with online social networks that support interactions among blatantly artificial personalities; look at the popularity of online gaming systems and Second Life. Still, online social and professional networks are seldom self-contained environments that exist only to promote online-only events, relationships, and transactions. For example:

- A network designed to support business relationships will usually have little value if it never enables its members to extend their interactions to business or professional relationships outside the online world.

- Primarily social networks frequently involve relationships among young people who go to the same school or who have family connections (e.g., cousins who live in different cities whose parents have family gatherings only on major holidays).

- Online networks built around volunteer social or political activity, even when they exist primarily to raise money, will often cross over into the “real world” by promoting meetings and real world activities related to fundraising and social or political advocacy.

Granted, a huge volume of business relationships already occur online among participants who never expect to see one another; chief examples include the buying and selling of packaged and commodity type goods where price and availability, not social relationship and trust, are paramount in the buying decision.

Nevertheless, any complete representation of social and professional networks must, in some fashion, incorporate a way to represent and accommodate real-world, physical, and person to person relationships, just as a public relations campaign targeting a varied population incorporates both “new media” and “old media.” Trying to tie these “outside network” relationships to online social networks can, however, generate potential privacy threats; see, for example, the controversy over Facebook and its “Beacon” process for capturing and selling non-Facebook transaction information. Such instances as this, however, are only the tip of the iceberg; data mining companies regularly gather and hook together data on individuals from various online sources. It is therefore not surprising that repositories of personal behavior information — such as Facebook — will look with hungry eyes at the money to be made from connecting personal with behavioral information.

All of this brings me back to the concept that I wrote about in one of my very first blog posts here: Identity Theft and the Licensing of Personal Information. We need better ways to control our own data. Those people who want to sell access rights should be able to do so. Those people who want to retain control over access to their personal data should also be able to do so. It is therefore likely in my mind that online social networks may arise that enable such control and this will serve as a powerful market differentiator.

Of course, an even more powerful market differentiator for online social networks will be when individual members begin to be paid for the sale of the personal data they are willing to reveal.

Copyright (c) 2007 by Dennis D. McDonald