Understanding How Open Data Reaches the Public

Introduction

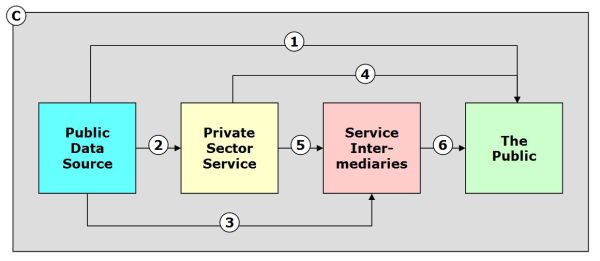

This model represents how public open data — data generated by or in connection with government programs that are available for release to the public — move from government agencies to the public via several different participants and channels.

Sometimes government agencies provide direct access (e.g., channel 1). At other times a mix of private sector services and intermediary organizations provide access (e.g., channels 4 and 6).

Surrounding them all are what I call “Channel C.” This “Collaboration Channel” consists of the social networks, collaboration tools, mobile technologies, and cloud based analytical resources that are now available to anyone with an internet connection.

System participants incur costs when moving data through these channels. Sometimes fees are charged for the work associated with this data movement. At other times participants absorb the costs associated with data management and transfer. How and by whom these costs are incurred and how they are recovered — if at all - is an important topic that is related to the sustainability of “open data” programs.

Figure 1. A Simple Model of Public Data Movement

Participants and Channels

Figure 1 displays 4 main participant classes:

- Public Data Source. A public data source is a government agency or program that gathers or generates various data types including textual, numeric, visual, geospatial, financial, and others.

- Private Sector Service. Private sector services include commercial and not-for profit organizations that receive, process, and redistribute government generated data, sometimes with “value adds” ranging from reformatting and standardization to analysis, commentary, and re-processing based on combination with additional data sources.

- Service Intermediaries. Service intermediaries obtain data from government agencies and private sector services and provide data access to the public. Intermediaries are especially important for large Federal government programs that operate through state and local governments or educational, health, or social welfare organizations.

- The Public. The public consists of individual, group, and organizational users that obtain and use — and sometimes redistribute — data that originate with government programs.

The numbered lines in Figure 1 represent the flow of data from data sources to the public. Some channels are direct (1) and some are indirect (e.g., 2—>5—>6).

I have incorporated Channel C, a “Collaboration Channel,” to model to represent the reality we now face in how information and data are shared. Conceptually, think of the Collaboration Channel as overlaying and pervading the entire system. Channel C data transfer can cut across organizational boundaries and represents the sharing of information among participants via available communication and collaboration channels including social media, collaboration networks, email, audio and video conferencing, text messaging, and online and cloud based data sharing services.

Use of such tools does not always respect organizational boundaries, nor are their costs and usage easily tracked, especially given the rising use for work of mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. Increasingly powerful cloud-based data analysis, modeling, visualization, and search tools have also become available and cost effective and provide additional avenues for analysis and sharing.

Assuming that control over data flow is possible by “traditional” organizations and their legacy database management governance — such as represented by the participant boxes in Figure 1 — is increasingly unrealistic. This reality needs to be taken into account when planning data access schemes that rely on communities of participants that may not share the same business models or economic or social interests. The overlaying Collaboration Channel incorporates social media, mobile technology, and cloud based data analysis and can support data sharing in ways that cannot be completely managed or controlled using traditional centralized governance structures.

Policy Implications

We need to understand how participants relate to each other in terms of the following:

- Data creation. Someone needs to be responsible for creating the data. Usually this is a government program or agency where data creation and management requirements are program driven. This is unlikely to change in the short term. As more programs become involved in open data programs the processes by which data are gathered and organized may need to be administered in a more consistent fashion.

- Governance. Over and above the role of the individual agency or program, there is value to understanding the overall process and how the different Figure 1 participants relate to each other. This may require a federated approach among participants if the actions of different organizations with their own governance hierarchies need to be coordinated. While there may be instances where structured and documented data can be “thrown over the fence” for third party distribution, instances might also arise where availability of the same data from multiple sources should be managed to minimize possible confusion caused by different versions of the same data set being made available by different sources.

- Finance. Costs will be incurred. Someone will need to be paid for data collection, processing, and maintenance of the original data to be shared. Decisions about chargeback, cost sharing, cost recovery, pricing, and who gets “free access” and what is provided for “free” versus for “fee” needs to be decided upon. Such decisions are difficult to crowdsource and will themselves require careful coordination, especially if commercial products are developed and sold that rely on taxpayer generated data.

- Standards. Standardization supports interoperability of data across systems. With data standards less time and money can be spent on data cleaning and structuring by participants and more on analysis, visualization, and interpretation. Who pays for imposition and monitoring of standards will also need to be agreed upon.

- Metadata. How data elements are defined, described, and indexed benefits not only from standardization but from agreements on semantics and how important concepts are defined. When multiple organizations are involved in sharing data, metadata standards and rules will need to be negotiated and coordinated as well, especially given the trend towards “shared services” in the Federal government.

- Legal requirements. Agencies and their programs exist and are re-authorized by Congress. There are legal requirements for program performance that will impact what data are generated and how data are used in the course of each program. Such legislation ultimately will influence what data are available and can be provided to third parties for redistribution.

- Service complexity. Data and the services they support are often intertwined. In some cases data will be a key component in defining program eligibility and performance. If data about individuals, their eligibility, and their use of program services are candidates for release by the source agency or for repurposing by third parties, mechanisms will need to be put in place to respect both privacy and sensitivity rules and regulations.

Implications

The “system” described above has many moving parts and represents an ecosystem where data collection, analysis, and distribution may not be responsive to strong centralized control. Also, the components in this system are already moving ahead with a variety of different efforts at standardization, public data access, and cost recovery. It’s a “moving train” as anyone who has watched the rapid growth of Data.gov can attest. Finally, it’s difficult to predict what kinds of innovations will evolve when the movement of public data through the system is promoted.

In the long run, traditional top-down efforts at management control may be insufficient to ensure that both agency goals and the potential benefits of open data access — including unanticipated but positive consequences — are realized in an efficient and cost effective manner. While leadership by the Federal government’s IT infrastructure will be necessary, it will also be necessary to ensure that ongoing efforts to advance open data access are managed efficiently both across agencies and in accordance with individual agency and program priorities. IT staff cannot do this on their own and will have to work closely with agency management.

One possible scenario is that open data access programs will continue to develop unevenly across the Federal government. Agencies with deeper traditions of data management and data standards will lead the way in making their data directly available to the public and through third party publishers and intermediaries. Other agencies will require more support in order to advance, even when prodded by OMB. Ultimately, decisions about “who pays for what” will have to be made in a complex environment impacted by sequestration and restricted budgets.

Copyright (c) 2013 by Dennis D. McDonald